Kaizen and Kaikaku

Kaizen. It is a word synonymous with improvement in organisations around the world. While the Japanese word literally means ‘improvement’, in industry and business the focus is on small, continuous steps to better processes. It is embedded in the management thinking of many organisations.

Japanese businesses developed Kaizen practices around the 1950s, most notably Toyota as part of their Toyota Production System. After studying why the company was so successful at high-volume production of high-quality vehicles in the 1960s, Masaaki Imai wrote several books on Kaizen and formed the Kaizen Institute, spreading the knowledge and practice around the globe.

However, there are times when Kaizen is not enough. Worse still, a small improvement can often hold an organisation back, perhaps even stifling significant development.

This is the Kaizen Paradox

In the 1980’s, author and business professor Oren Harari famously pointed out that not everything that exists could have been developed by continuous improvement alone. This idea is captured in another Japanese word that is less well known but equally important: Kaikaku.

Kaikaku means ‘radical change’. It describes the other side of improvement: the major step forward, or big leap. An analogy is a home illuminated by candles; while Kaizen improves upon the candle, Kaikaku is the installation of electric light.

Kaikaku is a less famous but equally important part of the Toyota Production System and is often overlooked by organisations in their rush to embrace Kaizen.

The Kaizen Paradox and the issues it creates

Small improvements commit resources that could be better spent toward a larger step forward in performance, or with more strategic planning, could have contributed to a major change.

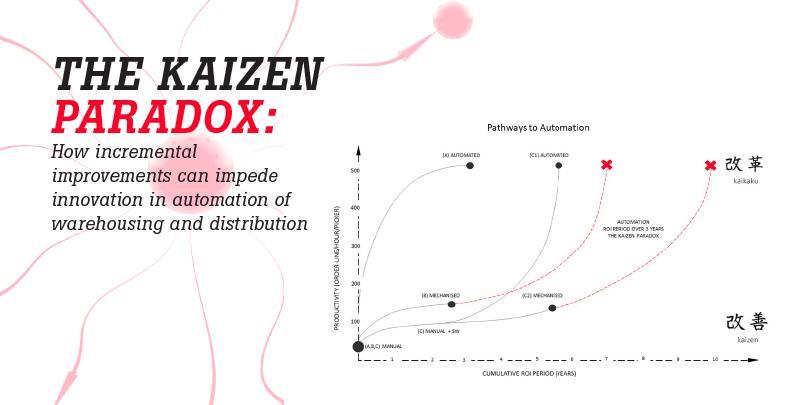

Finally, when a Kaikaku opportunity exists, the Kaizen path weakens the Kaikaku ROI and productivity can plateau at a lower level. This is the Kaizen Paradox at work.

Paradox in practice

In a recent real-world example, a company was seeking to identify a solution for an automated ‘goods-to-person’ warehouse in a bid to achieve a significantly higher level of business performance.

However, a year earlier the company had invested in a mechanised ‘zone–to-zone order picking’ solution, consisting of conveyers and carton storage shelving.

Although the project was still in the commissioning phase, senior management could see that the solution wasn’t going to meet their long-term requirements. Fortunately, the mechanised solution didn’t occupy the entire warehouse, making it possible to build an automated goods-to-person solution on the same site.

Developing a business case for a goods-to-person automated solution, the company gathered quotes to either move the zone-to-zone solution, redesign it, or scrap it altogether.

It soon became clear that the mechanised system made it much harder for them to proceed with the automation they required, as the business had invested a large sum on a now largely redundant piece of equipment that occupied a prime position in the warehouse. Unless the mechanised system could become part of the fully automated solution, the company also faced the cost and embarrassment of scrapping the new installation.

While the mechanised system improved productivity from 50 to 150 order lines per hour per person, the automated goods-to-person system would deliver 500 order lines per hour per person. As a result, almost a third of the productivity gain that would have been realised in going from a manual to an automated operation was already delivered by the mechanised system. This worsened the business case, extending the ROI of the desired automated system by an extra year. Because the mechanised system could not be incorporated in the automated solution, there was no reduction in the cost of the required automation.

This is just one example of the Kaizen Paradox, which is a common predicament for many businesses, where investments are made to achieve productivity gains, but in doing so they dilute the business case for a better investment, causing them to plateau at a lower level of productivity.

Tools and approaches to support best practice

Both manual and mechanised warehouses involve ‘person to goods’ in some form. The difference being the way the order tote moves around the facility, trolley or picking truck to conveyor, and the addition of WMS software to control order picking more efficiently. These improvements have helped reduce the time between pick operations and gradually lift productivity from around 50 to 150 order lines per hour per picker.

The Kaikaku occurred when goods-to-person technology was developed that radically transformed the way orders were picked, allowing a stationary worker or a robot to pick from products delivered to them in sequence. This can typically boost individual picker performance to between 500 and 1,000 order lines per hour and minimise the labour required, while at the same time significantly reducing the warehouse footprint due to higher density storage.

An automated goods-to-person warehouse can typically achieve the same throughput as a manual or mechanised operation, with around half the staff and in half the building size. As a result, a strategic approach to automation can save significantly on the cost of warehouse expansion or remove the need for relocation, prolonging the life of the existing facility.

This more strategic approach to Kaikaku can protect an organisation from being trapped in a focus on low performance operations. Being cursed with the Kaizen Paradox.

Next steps for boards and managers

For successful organisations, major leaps forward in performance are often approached strategically. Kaikaku investment are made before Kaizen improvement.

Every business is striving to improve, but not all improvements are complementary or equal. Opportunities to stay ahead of the competition can be stalled by an organisation’s own efforts. Critical to enduring competitiveness are a regularly reviewed strategic approach to improvement, and a long-term strategy to deliver.

The Kaizen Paradox is a common predicament for many businesses, where investments are made to achieve productivity gains, but in doing so they dilute the business case for a better investment, causing them to plateau at a lower level of productivity. Once organisations are aware of the potential for investments that create a Kaizen Paradox, they are better able to consider potential improvements as part of a bigger, longer-term picture.

By Paul Stringleman,

Senior Consultant, Swisslog.

About the Author

Paul Stringleman is a Senior Consultant at Swisslog. He began his career in intralogistics 20 years ago in Tokyo, Japan and has spent 15 of the last 20 years living abroad and designing large-scale automated systems for airports and distribution centres. In the past five years, Paul has developed several data driven automated warehouse solutions for e-commerce/retail companies in Australia.